People

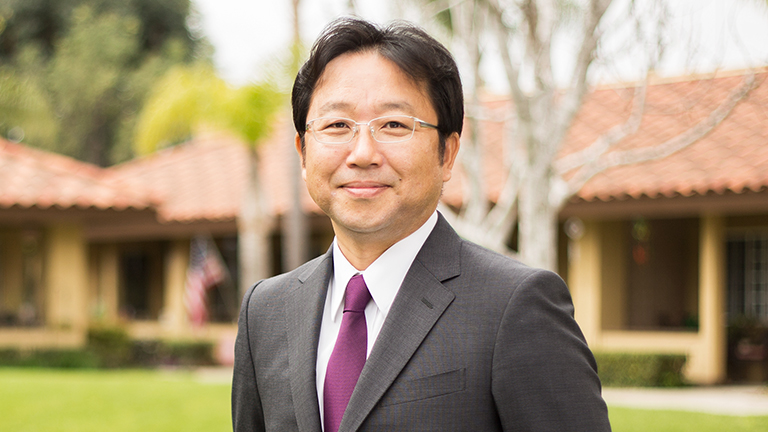

Yuki Yashiro

Zalar Holding S.A.

Directeur Chargé de Mission

Morocco is a fast-emerging African nation. While addressing rising demand for animal protein in the country, Yuki Yashiro is also looking beyond to a vision of his own: a world free from poverty.

Chicken: Animal protein with few religious taboos and minimal environmental impact

I work in the poultry-production business in Morocco. I’ve been here for just over two-and-a-half years now.

There are worries about a future possible “protein crisis,” when the supply of animal protein is no longer able to keep up with the rapid increase of the human population. Poultry production represents one of the solutions to that problem.

Low environmental impact and fewer religious restrictions are what make chicken special. Given that Muslims are forbidden from eating pork and Hindus from eating beef, chicken’s potential is obviously high.

Normally, I work in the Zalar office in Casablanca, Morocco’s business capital. Zalar is the biggest integrated poultry producer in the country; Mitsui has a stake in it. Zalar does everything from grain trading and making animal feed to hatchery, broiler farming, and slaughtering and meat processing.

Zalar itself is a holding company with around 10 subsidiaries spread across its five businesses. I spend a lot of my time on the road visiting the company’s different facilities. I look for places where there is room for improvement and share the data on animal-feed production, chicken farming, slaughtering and processing with my counterparts in Japan. I also scour Mitsui’s network to find new partners who can collaborate with Zalar on developing solutions.

Basically, I act as a sort of hub for Mitsui’s efforts to help upgrade every aspect of the business.

Japanese-style fried chicken comes to Morocco

What was my hardest and what was my happiest experience in this job? Funnily enough, I think my answer to both questions is probably the same. The hardest and happiest thing for me is something I’m working on right now, the Karaage Project.

I was keen to create and market a new frozen product—Japanese-style fried chicken, known as karaage in Japanese. My aim was to make a high value-added product that other companies in Morocco couldn’t copy. Getting there has been anything but straightforward!

Since Zalar doesn’t have its own frozen-food production equipment, the first thing I had to do was to find a partner. Of course, when I brought up karaage with potential partners, no one even knew what I was talking about! Finding someone to work with us was a challenge, both because the product itself was unfamiliar and because the firms we approached were worried about possible contamination of their production facilities with foreign material.

The approach I took was to start off with something familiar—frozen chicken nuggets—and then take it from there, one step at a time. Now you may think there’s not much difference between chicken nuggets and karaage chicken, but from the manufacturing perspective, the difference is actually massive. Nuggets are made of deboned, ground-up chicken meat and are all the same shape, size and weight. Karaage is chopped pieces of meat of all different shapes and sizes. It also has a distinct marinade seasoning, so it is far more difficult to make.

In Morocco, people have their own way of doing things, which they’re justifiably proud of. It was important for me to respect their perspective while also slowly earning their trust and understanding. The route I took to making karaage was slightly roundabout, but it was also completely necessary. I can’t tell you how happy I felt when my counterparts, who had all been rather skeptical at the start of the project, tasted the prototype karaage and declared it to be delicious. We’re now in the very final stages of commercialization.

Harsh life lessons as a student volunteer in Nairobi

While I was at university, I worked in Kenya as a volunteer teacher. I took a year off to work at a Nairobi orphanage, where I taught math and looked after the kids.

As a boy, I’d always dreamed of working for the UN; then in junior high I read a book which really inspired me with the idea of a poverty-free world. That was my reason for going to Kenya. I wanted to see if the idea was feasible and what I personally could do to make a contribution.

I had two life-changing experiences during my stay.

The first was to discover that not even the brightest and best-qualified young people in Kenya could find “real” jobs. I was friends with quite a few people from the country’s top universities. At that time, it was difficult for them to find the kind of jobs they wanted, and they ended up choosing to work for international NGOs more through a process of elimination than anything else. No matter how hard they studied, there weren’t many avenues for them to put their skills and knowledge to use for the benefit of their country. That’s why there’s a 'brain drain' in Kenya. My takeaway was that aid alone isn’t good enough; you’ve got to create real businesses that create jobs.

My second life-changing experience was getting mugged. One day, this gang of six or seven kids came up behind me and attacked me. They knocked me to the ground, punched me, kicked me, took my wallet and passport, and left me with nothing.

That was a massive psychological shock. There I was, feeling quite pleased with myself about what I was supposedly “doing for Kenya,” and now the country seemed to have rebuffed me. It felt like a repudiation of everything I was thinking and trying to do.

The fact that the kids who mugged me were my age only made the shock worse. But as time passed and I calmed down a little, I started asking myself whether those kids and I were so different after all. If I was in their position, I might well have done the same thing myself.

When things are hard, people are forced to make hard choices just to stay alive. I’m Japanese. Was there something that I, as a Japanese, could do to give kids like the ones who mugged me more life choices, like, say, launching a business with them and creating jobs? That was the thinking that led me to join Mitsui.

Zalar employs about 3,000 people. I think my university self would be proud to see that I’m now being of some practical use to Moroccan society as a member of the Zalar team.

Making a reality of a world without poverty

In terms of the poultry business, my first goal is to make the karaage project a success. We’re nearly at the finish line, and I can’t wait to see Japanese fried chicken on the store shelves. This will be a first not just for Morocco, but for Africa as a whole, I think.

Longer term, we are hoping to start exporting chicken to West Africa, the Middle East, and then to Europe. Geographical proximity to all these places is one of Morocco’s advantages. When it comes to building up export markets, Mitsui’s network should play a significant role.

Beyond that, I have my own goals: one is to create employment opportunities in Sub-Saharan Africa via the poultry-farming business. There’s nothing I’d like to do more than expand the business there and help bring down poverty levels by creating jobs.

In the long run, I also have a dream of one day helping to alleviate poverty in Kenya through the business I’m involved in. Doing so would bring my experiences from when I was a university student full circle. I know there are poorer countries in Africa, but I have an emotional bond with Kenya.

The Kenyan capital Nairobi is home to Kibera, East Africa’s biggest slum. I’ve always dreamed about being part of a business big enough to help consign the word slum to the dictionary of dead words for all of Africa!

Lots of things—my world view when I was a junior high school student, the harsh realities I had to deal with while at university—made me the person I am today. I want to hold on to those old original attitudes and emotions. As I make my way forward in life, I always try to remember where I came from.

Posted in Feb 2025