Mitsui & Co. Global Strategic Studies Institute

ASEAN Adapting Its Course to Realities

Sep. 9, 2016

Daisuke Shintani

Asia, China & Oceania Dept.

Mitsui Global Strategic Studies Institute

Main Contents

The ASEAN Communities were formed at the end of 2015, whereby ASEAN entered a new era. The Communities have not been as unified as initially envisioned, however, and are facing challenges that could possibly shake their philosophy on the diplomacy and security fronts. With each member state saddled with concerns over its own domestic political system, a red flag has been raised regarding the realization of ASEAN’s ideals.

The Realities of the ASEAN Communities

While tariff elimination has progressed as planned in the ASEAN Economic Community (AEC), a pillar of the ASEAN Communities, liberalization in the services and investment fields has been delayed. Quite a few member states are even establishing new non-tariff barriers, to say nothing of reduction of the existing ones. Let us examine the situation in comparison with the EU. While the EU aims to be a community with stronger binding powers, with each member state delegating to the EU part of its sovereignty, including the right to currency issuance and taxation, in the case of ASEAN, non-intervention is the principle and much is left to the discretion of each member state. As a result, in ASEAN, each member state’s convenience often takes precedence over the greater goal of community integration. In fact, many ASEAN member states, including Myanmar, the Philippines, Thailand, and Malaysia, have presently no choice but to give higher priority to domestic issues over the Communities due to their respective internal political concerns. Although ASEAN laid out a new set of goals toward 2025, with a view to further strengthening the Communities, which were launched at the end of 2015, as stated above, the timeline for achieving these goals was not included therein, and accordingly, the project took a step back, only to fall in line with the current realities of ASEAN (Table 1).

South China Sea Issue and Terrorism Risk

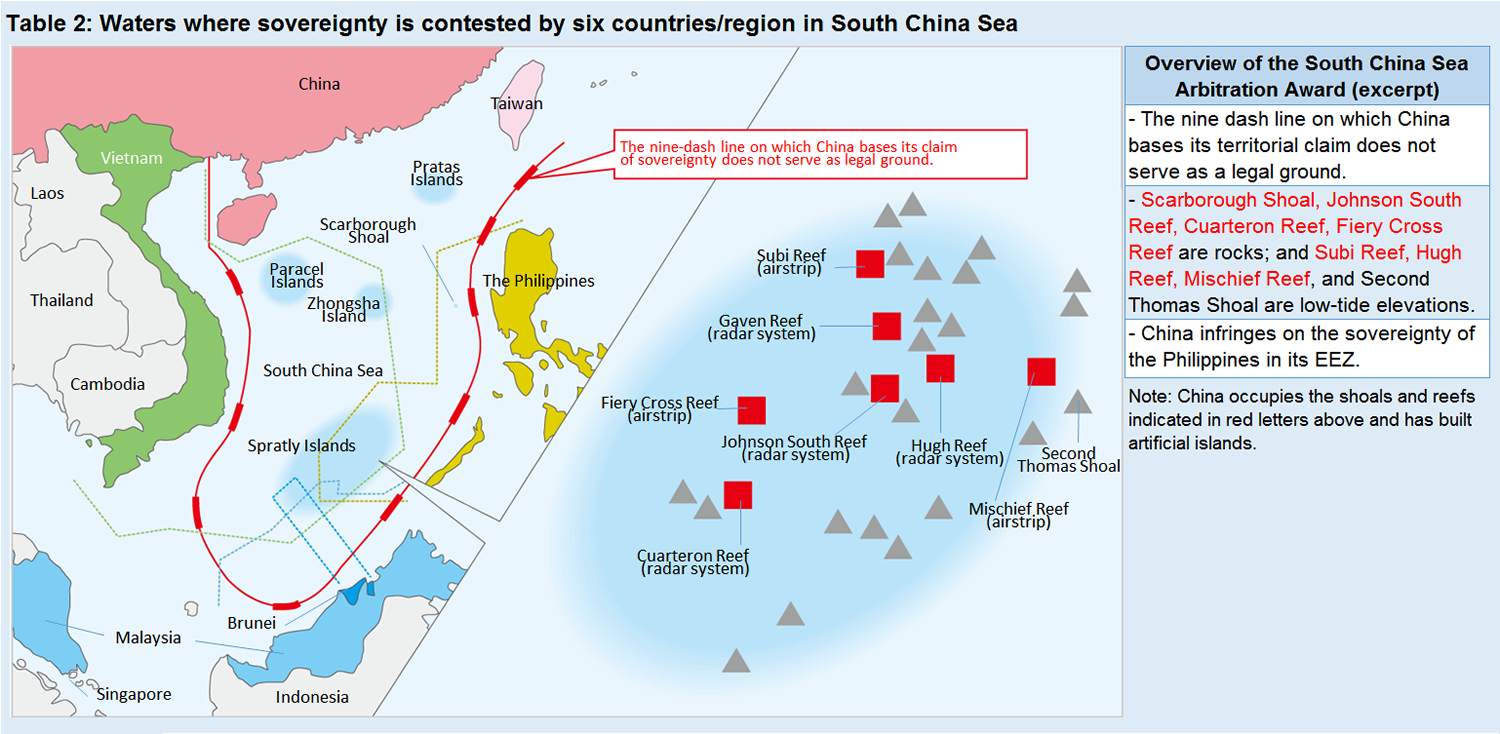

ASEAN is also faced with an issue that could shake the Communities’ unity. Generally, ASEAN member states have enjoyed strong economic relationships with China in recent years. For example, China is the biggest trading partner for three member states in terms of imports, and for seven member states in terms of exports (20151). Quite a number of member states, including Cambodia, which is regarded as pro-China, have received cooperation from China in infrastructure development projects. Another recent example is China’s receiving orders related to an expressway construction project in Indonesia. On the other hand, however, four member states2, including the Philippines and Vietnam, are embroiled in conflicts with China over sovereignty issues in the South China Sea (Table 2).

ASEAN has failed to take a unanimous stance toward China’s escalating moves in the South China Sea, including the construction of artificial islands and installation of drilling rigs. The award in an arbitration case filed by the Philippines with the Permanent Court of Arbitration, which was announced on July 12, 2016, is a de facto denial of the grounds on which China lays its claim of sovereignty, and entirely accepts the Philippines’ case. Meanwhile, Cambodia and Laos announced their decision not to support the award, even prior to the announcement thereof. Furthermore, a joint announcement released following the meeting of foreign ministers of ASEAN member states in July did not include any comment on the award. Each ASEAN member state has a policy to separate politics and economics, and accordingly, they treat political/diplomatic issues and economic issues with China separately. It is certain, however, that the varying degree of strength of the relationships with China is the factor shaking the unity of ASEAN as a community, and will likely continue to be one of the biggest obstacles to the promotion of the ASEAN Communities.

Another big challenge is the growing influence of the so-called Islamic State (IS) in ASEAN member states. Terrorist bomb attacks were perpetrated in Indonesia in January 2016 and in Malaysia at the end of June 2016, in both of which IS was involved. These two cases are considered to have been orchestrated by citizens who had moved to Syria to become combatants. Malaysia is said to have been a recruitment base for IS combatants in Southeast Asia for a while. IS is also said to be bolstering relationships with extremist groups in ASEAN countries, such as Jemaah Islamiyah (Indonesia) in recent years. In the Philippines, a group claiming to be a branch of IS released a message urging terrorist attacks in three countries. A terrorist attack plot in Singapore also surfaced. As seen in these developments, the threat of terrorism is growing. Although the ASEAN Communities claim to work together under the framework of the ASEAN Political-Security Community (APSC), on the front of cooperation on security issues, countermeasures against specific threats of terrorism are left to individual member state’s discretion. Amid the growing risk of cross-border terrorism, including the crossing of borders by terrorists and direct attacks from neighboring countries, ASEAN is faced with the urgent task of addressing security issues on a unified basis.

Myanmar: Lack of Human Resources Coming to Surface

When we look at each ASEAN member state, it is evident that quite a few of them are vexed with domestic issues. Let us take Myanmar as an example. Although a civilian government was formed at the end of March of this year for the first time in 54 years, concerns following the general election are becoming realities. The new government carried out “100-day plans” soon after its inception to identify tasks necessary to implement reforms. As a result, a set of economic policies consisting of 12 agendas, the first of its kind from the new government, was announced on July 29 (Table 3). The policies lacked details, however, and disappointed many. Accordingly, the business world is strongly urging the government to draw up a master economic plan, including roadmaps and others details.

The National League for Democracy (NLD) is said to be facing the following issues: (i) reconciliation with ethnic minority militant groups, a ceasefire with which was not reached under the previous government, and (ii) the ability of Ms. Aung San Suu Kyi (who assumed the post of foreign minister) to conduct diplomacy, and to make and implement various policies. In addition, there are two issues concerning a shortage of human resources, which are thought to have a particularly significant impact. The first is that the NLD itself definitely has a shortage of human resources for leading the government. Considering that only blanket economic policies were released after four months, NLD probably does not have sufficient staff capable of drafting and implementing economic policies. The second is the shortage in human resources resulting from the collapse of the country’s education system. Institutions to train and educate highly skilled people were dismantled in Myanmar during the days under military rule, as typified by the dissolution of Yangon University. As a result, Myanmar does not have a sufficient number of trained mid-career workers in their 30s and 40s. Accordingly, the country is utterly in want of human resources that can lead industries, let alone politics. Furthermore, there do not seem to be sufficient strategies to train people who will take the lead in industries, as evidenced by a package of industrial policies, including an economic corridor plan, which were announced by the Ministry of Industry on July 22 and whose action plan has not yet been formulated. These human resource shortage issues may well cast doubt over the sustainability of the NLD government. Although Myanmar has reached a major turning point in terms of democratization, when the country comes to nation building, it is faced with huge challenges.

Thailand, Malaysia: Burdened with Domestic Issues

Some member states are being shaken by domestic politics. In Thailand, which has been governed by a military junta since a coup d’état in 2014, a system whereby the military will be able to engage in politics even after the future transition to civilian rule is being created. The junta held a national referendum on the new constitution draft on August 6, 2016 (voter turnout: 59.4%), and as a result, the draft was approved by a 61.35% majority. Military rule is slated to be replaced with civilian rule after a general election in 2017. Under the new constitution, however, members of the Senate will in effect be chosen by the current junta. Moreover, since the powers of the Senate have been reinforced, even if the red-shirts camp (i.e., Thaksin supporters), which is strong in the general election, wins the elections of the members of House of Representatives, its influence will be limited. In addition, the new government will be required, under the new constitution, to implement its policies in accordance with the reform plan formulated by the current military government. Thai citizens have chosen stability under the military rule, and accordingly, the regression of democracy is unavoidable. With the current situation as described above, Thailand cannot possibly be a country that can lead the ASEAN Communities.

In Malaysia, opposition parties made a leap forward in the general election in 2013, and the regime of the current governing party, United Malays National Organization (UMNO), which has been in power since the country’s independence, is beginning to decline. There are growing calls to hold Prime Minister Najib accountable, triggered by the corruption allegation concerning the government-owned investment company 1Malaysia Development Berhad (1MDB). Despite the efforts of the former Prime Minister Mahathir to bring down Prime Minister Najib, presently, Prime Minister Najib has a strong power base within UMNO. Also, the governing party scored a landslide victory with 70% of the vote in the local elections held in the state of Sarawak in May 2016. Accordingly, the influence of Mr. Mahathir has remained limited so far. Prime Minister Najib might well go ahead with an early snap election3 to solidify his base, in which case, political turmoil could be expected.

Expectations and Concerns Surrounding the Philippines, the Next ASEAN Chair

The Philippines, the ASEAN chair in 2017, will be a touchstone to divine the future of ASEAN, which is currently in a transitional phase. Philippines’ President Duterte, who assumed office on May 9, is firstly focusing on anti-crime measures, a pillar of his campaign pledges, thereby arresting drug criminals one after another, sometimes even killing them at a crime scene. Despite strong criticisms against his methods from within and without the country, he has been enjoying support from Philippines citizens, as evidenced by a recent poll4 indicating his approval ratings at as high as 91%. Meanwhile, Duterte’s government announced economic policies that adhere to those of the former President Aquino’s government, including an increase in foreign direct investments. The Duterte’s government also expressed an intention to increase investments in infrastructure to the amount equivalent to 5% of the national GDP (to be raised to 7% in the future). The business world has welcomed these initiatives, and, overall, his government seems to have started off smoothly.

Meanwhile, ASEAN member states are not on the same page when it comes to the South China Sea issue. Amid this situation, how President Duterte, who has solidified domestic support, will reestablish diplomatic relationships with China is worthy of attention, as it is expected to largely influence the direction of the Philippine’s ASEAN chairmanship. Now that President Duterte expressed his support for the award by the Permanent Court of Arbitration, there is less chance of the Philippines shelving the award and coming closer to China. For the Philippine government, closing the diplomatic distance with China could be risky as it might generate resentment among Philippine citizens. President Duterte’s future policies concerning China will likely affect the direction of the ASEAN Communities.

- Direction of Trade Statistics, IMF.

- Six countries/region in total (namely, China, Taiwan, the Philippines, Vietnam, Malaysia, and Brunei) are claiming their sovereignty.

- The next general election due to termination of the term is slated for 2018.

- Poll conducted by the local private research firm Pulse Asia Research, Inc. in early July 2016.