Mitsui & Co. Global Strategic Studies Institute

EU Unity Is Being Tested by an Increasingly Confusing Refugee Problem

Apr. 8, 2016

Yosuke Inuzuka

Europe & CIS Dept. Mitsui Global Strategic Studies Institute

Main Contents

EU unity is being shaken, confronted by a refugee problem with no end in sight. In 2015, over a million people seeking refugee status pushed into Europe from the Middle East, Africa, and Asia. People seeking refugee status1 aim for Germany and northern European countries, which have substantial systems for taking in refugees, and mainly take routes from Greece through the Balkan Peninsula or central European countries. However, concerned about prolongation of stays and worsening of public security, the countries involved have laid out their own border control systems and restricted “freedom of movement,” and the symbol of EU unity, the Schengen Agreement,2 has become in part an agreement in name only. Immigration restrictions have left roughly 50,000 people stranded in a bad environment in Greece, and the refugee situation seems set for an unavoidable descent into a serious humanitarian crisis. Will the 28 EU countries be able to let go of national self-interest and come together to find a “European Solution?” The EU is being put to the test.

“Freedom of movement” shaken by an explosive inflow

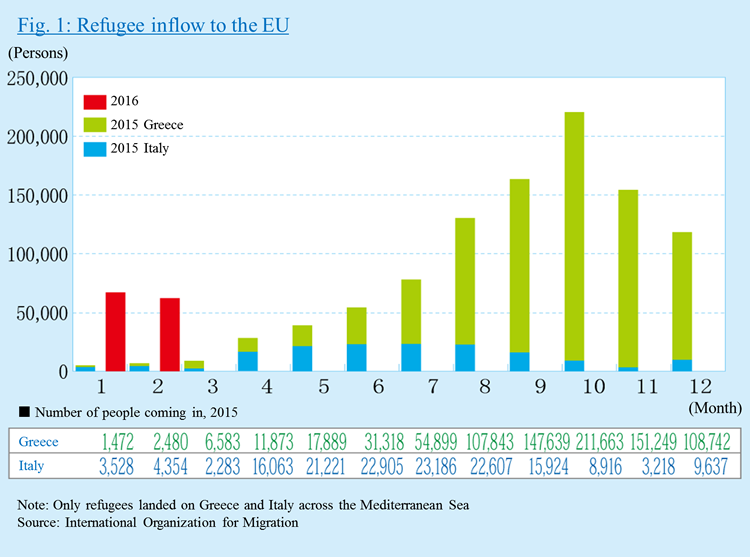

The flow of persons seeking refugee status into Europe increased rapidly beginning in the summer of 2015 (Fig. 1). The civil war in Syria intensified from March 2015, and some of the roughly 4.8 million who fled the country sought to enter Europe through Turkey. In response to a larger than expected influx, Central European countries restricted entry and exit. However, since Germany, which takes pride in being a leader of the EU, announced simplified measures for taking in asylum seekers, including relaxing the EU Dublin Regulation that stipulates the procedures for recognition of refugee status, people seeking refugee status aiming for Germany flooded into Europe.

According to Eurostat, a record 1,255,640 people applied for refugee status in the 28 EU member states in 2015. Applications to non-EU countries such as Albania and Kosovo are also included in these statistics, but even so, one understands how explosive an influx this is. There were about 362,800 applicants from Syria, 178,200 from Afghanistan, and 121,500 from Iraq. The largest number of applications, 441,800, has been filed in Germany3 (a 155% year-on-year increase), followed by 174,435 applications filed in Hungary (up 323%), and 156,110 in Sweden (up 108%). Applications to these top three countries accounted for about 62% of all applications.

Starting in September 2015, at least 10 Schengen Agreement countries including Germany confronted with huge inflows implemented immigration controls in succession and are now restricting freedom of movement. On February 17, Austria announced that it had reached its limit and would be limiting its acceptance of refugee applications to 80 persons per day. Claiming the country violated the Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees, the EU demanded that the limit be withdrawn. Countries such as Slovenia and Croatia, as well as non-EU member states Serbia and Macedonia, have indicated their plans not to accept the entry of refugee status seekers in principle, and for all intents and purposes, the Western Balkans route has been closed (Fig. 2, as of March 23).

In particular, Macedonia’s de facto closing of its border with Greece has heightened the danger of the refugee problem descending into a full-blown humanitarian crisis. Due to their exit being closed, over 50,000 people have accumulated at camp facilities in harsh conditions in Greece. These camps on the border with Macedonia have only 24 showers and 140 toilets per 15,000 residents, and there have been reports of dysentery. Food and water shortages are also severe, and conditions will certainly worsen further over the summer if nothing is changed. Unfortunately, the interest of other EU member states and surrounding countries is in preventing the inflow of refugees into their own countries, and the pace of assistance remains in disorder.

Anxiety over enforceability of the EU-Turkey Agreement

With no end in sight to the Syrian civil war that is the root cause of the problem, the only thing that could be done to avoid a fresh new “Greek crisis” would be to stop the inflow from Turkey. On March 18, the EU and Turkey agreed to new countermeasures centered on this agreement: in exchange for Greece sending back to Turkey all refugee status seekers who arrived in Greece from Turkey, the EU would accept, based on screenings, from among the 2.7 million Syrian refugees residing in Turkey, only the number of people who were sent back to Turkey, up to a maximum of 72,000.

With the new agreement, the EU aims to restrict chaotic inflow of stowaways, while simultaneously excluding a group that accounts for about 60% of those seeking refugee status--those who wish to enter but will have difficulty being recognized as refugees--and controlling the inflow of true Syrian refugees coming via the Turkish route. If it succeeds, then the immigration controls introduced by each country will become unnecessary, opening a path to restoring the Schengen Agreement to its original conditions. Both sides also agreed in November 2015 that in exchange for 3 billion euros in aid, Turkey would introduce measures to strengthen enforcement against stowaways, but the recent agreement is more in-depth in content.

The question is whether or not the effectiveness of the agreement can be ensured. First of all, although with Germany’s leadership, the EU made a resolution that its member states would jointly accept a total of 160,000 people seeking refuge status by September 2015, various Central European countries have refused to receive them and an East-West confrontation in the region has been radicalized. A provision in the recent agreement also clearly states that no new obligations will be imposed on member states, illustrating the strong cautionary feelings of the Central European countries. There has also been a rise in anti-immigration forces, and other countries are unenthusiastic about sharing the burden. Realized transfers amount to only 1,100 people (as of March 31). Unless the sharing of the burden of acceptance is accelerated, the agreements with Turkey will amount to mere castles in the air.

Feelings of distrust toward Turkey among certain EU member states are also deep-seated. With the recent agreement, Turkey won a doubling of the already-agreed-to 3 billion euros. In addition, Turkey is demanding that the EU visa exemption for Turkish nationals that was to be realized by October 2016 be moved up to June, and that its negotiations to join the EU be accelerated. Doubts are arising over whether Turkey isn’t slackening its border security and overlooking the inflow of refugee status seekers to exert pressure on the EU, depending on circumstances.

Strengthening security at national borders outside of EU territories to block inflow from Turkey at the water’s edge is also an important and pressing challenge. Currently, the EU is discussing greatly strengthening the role of Frontex (European Agency for the Management of Operational Cooperation at the External Borders of the Member States of the European Union), which now plays only a coordinating role among member state agencies concerned with border control, and is discussing a reform proposal centered on the establishment of a proprietary force of 1,500 officers. It is also asking Greece to submit an action plan for extra-regional border security, but the concrete actions will begin in May at the earliest. At present, NATO warships are on the lookout for stowaways, but it is unclear whether an effective surveillance system can be worked out soon.

Pressing issues: Germany’s increased burden and deepening divisions

Even so, the EU does not have effective measures to curtail inflow other than the agreement with Turkey. Although there may be twists and turns, in the end, it will be pressed to execute the agreement step by step. If chaotic inflow expands as is, at some point other member states will be drawn into the maelstrom of confusion. It would be impossible for Greece, with a population of 10.8 million, to take on all of the refugee status seekers. Although the agreement with Turkey is not the best agreement, it can be expected to have temporary inflow curtailing effects.

However, it is impossible to prevent inflow by completely closing off sea routes, and the inflow of people seeking refugee status is probably unavoidable. By agreement, the EU will take in an equivalent number of Syrian refugees from Turkey, but it is unlikely that all member states will share the burden. In the end, in order to fulfill the agreement, it is likely that some volunteer countries, centered on economically powerful Germany, will be asked to bear the burden. As the refugee problem, which is supposed to have sought a “European Solution,” transforms into a “German Solution” in the process, side effects, such as opposition from the German people and a decline in Chancellor Angela Merkel’s centripetal force, are expected to be vividly manifested. At the three-state German assembly elections held on March 13, the anti-immigration rightist Alternative for Germany party (AfD) made considerable gains. In addition, opposition by member states who have openly made their interests clear is deepening regional divisions, which can only invite a further drop in the EU’s centripetal force. We are heading toward a crucial moment for the deepening of unity sought by the EU.

- A “refugee” is defined in the 1951 Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees as “A person who owing to a well-founded fear of being persecuted for reasons of race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group or political opinion.” Moreover, although not applicable to a refugee under this convention, the EU recognizes a stay by a person who can expect to be inflicted with “serious harm” upon returning to his/her home country, considering such a person a “beneficiary of subsidiary protection.” People that pose as Syrians or others who can easily gain refugee status and wish to immigrate for economic reasons (such as to find work) are referred to as “economic refugees,” and are in fact immigrating illegally.

- This agreement on the freedom of movement of persons was signed by 26 countries, and eliminates border checks within the region. Two of the 28 EU countries, the United Kingdom and Ireland, have not signed the agreement, while at present the participation of Romania, Bulgaria, Croatia, and Cyprus has not been authorized. Non-EU countries that are members of the agreement are Switzerland, Norway, Iceland, and Lichtenstein.

- The German Federal Ministry of the Interior, etc., announced that 1,091,894 people seeking refugee status entered the country in 2015. This figure is based on the number registered in the EASY System, which is designed to fairly allocate refugee status seekers to each German state. However, since some refugee status seekers have made multiple registrations with the EASY System in order to be sent to their desired state, and there are also many cases of people subsequently leaving for a third country, it is difficult to consider this an accurate number that indicates the number of refugee status seekers residing within Germany. In February 2016, the Ministry of the Interior stated that out of roughly 1.1 million who had registered with the EASY system, the whereabouts of at least 13% (about 140,000 people) were unknown. It is also pointed out that the number of persons whose whereabouts are unidentifiable could rise to a maximum of 600,000.