Mitsui & Co. Global Strategic Studies Institute

NAFTA Renegotiations: A Long Way to Complete the Process

Oct. 4, 2017

Ryohei Yamada

North America & Latin America Dept.

Mitsui & Co. Global Strategic Studies Institute

Main Contents

The Historical Context of Renegotiation

On August 16, 2017, the Trump Administration had the first round of renegotiations over the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), in line with its pledge "to renegotiate NAFTA, or withdraw from it" as one of the top priorities of the president’s trade policy agenda. Some chapters of the 23-year-old NAFTA is outdated by global changes such as the development of electronic commerce, and needs to be updated.

NAFTA renegotiation rounds are on a frequent schedule, with six to seven meetings to take place by the end of 2017. NAFTA renegotiation is not advocated by the Trump Administration for the first time. Back in the 2008 presidential campaign, several Democratic candidates insisted on the need to renegotiate NAFTA; however, the Obama Administration did not take any action after its inauguration. The Office of the United States Trade Representative (USTR) later explained that TPP, which late included Canada and Mexico, was positioned as President Obama’s promise to renegotiate NAFTA. Aside from President Trump’s provocative expression describing NAFTA as the “worst trade deal ever made,” the current Administration may deserve credit for having actively initiated negotiations.

However, it is difficult for the Trump Administration to achieve its goal of reducing trade deficits. An FTA alone is not sufficient to change the overall trade balance between nations. Some point out that, even if the terms of the agreement were to reduce a trade deficit with Mexico, the imports from Mexico would only be replaced by goods from other countries such as China, merely resulting in an increase in trade deficits with them. In addition, even if negotiations are concluded, it takes a certain period of time up to ratification. It takes a while before the agreed terms will be implemented. Amid these situations, the Democratic Party is claiming that the Trump administration, which criticized the TPP agreement and pulled the US out of the deal, deliver something different from the TPP. Democrats are prepared to criticize the administration once NAFTA turns out to be no different from the TPP agreement.

Withdrawal from NAFTA Is for the US Side to Lose

US Trade Representative Robert Lighthizer officially advocates a "do-no-harm" approach as a renegotiating principle. US industrial circles support this approach and do not expect any change in the trade-deficit mechanism. If negotiations move forward with this approach, extreme development -- such as the withdrawal from NAFTA -- should not happen. Cabinet members outside the negotiations, including President Trump and Secretary of Commerce Wilbur Ross, may use the withdrawal as a negotiating tactic; however, a withdrawal would not bring any benefits to the US, which is perceived by even its negotiating partners. Since Congress is not at all supportive of the US withdrawal, the Trump Administration, if determined to make it a reality, would have to exercise its own discretion.

Article 2205 of NAFTA specifically lays out the withdrawal, stating that one of the three countries “may withdraw from this Agreement six months after it provides written notice of withdrawal to the other Parties.” This allows the US Administration to notify the other parties of its withdrawal at its own discretion. However, the implementing legislation passed by Congress in 1993 is another story. In the US, an FTA is formed on the agreement concluded with its partner countries and the implementing legislation -- the domestic laws amended to implement the concluded agreement. The US withdrawal from an FTA generally does not mean the automatic repeal of the implementing legislation. In order to completely withdraw from an FTA and revert to the tariff level without it, the implementing legislation needs to be repealed. However, there is no definite interpretation of what is required to repeal the laws -- whether it requires no more than executive discretion or Congressional passage of another bill. Different opinions exist over the range of discretion of the executive branch, such as repealing just tariff measures or also non-tariff measures. Even if Congress passing a bill is interpreted as necessary, there is no chance that Congress will respond to such request. Then, even after the US pulls out of the FTA, US imports could still be subject to FTA tariffs.

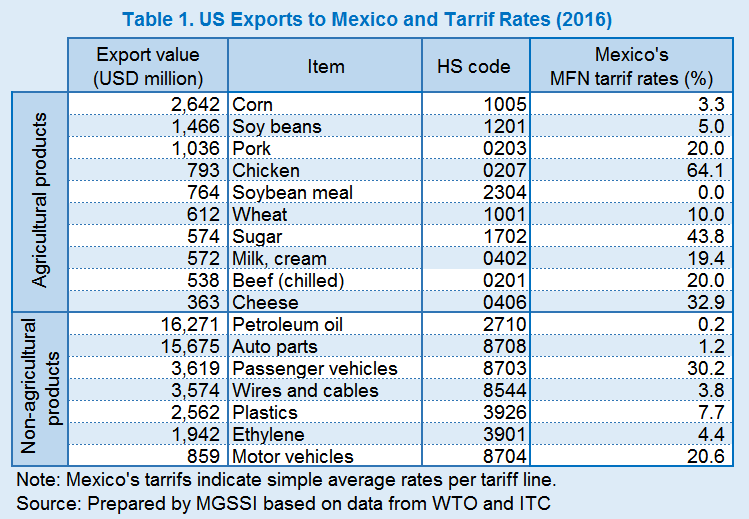

Putting the interpretation issue aside, if the Trump Administration were to successfully pull the US out of NAFTA and finally revert to a pre-FTA tariff level, the WTO’s most favored nation treatment (MFN) tariffs would be imposed on goods to the US from Canada and Mexico, as well as Japan and China. The Trump Administration might be satisfied with a possible decrease in imports because of higher US tariffs, but it is more important to note that Mexico' tariff will also be raised to MFN levels, most of which are higher than the US rates. The average MFN tariff rates for all goods are 3.5% in the US and 7.0% in Mexico, and for agricultural products, the rates stand at 5.2% and 14.6%, respectively. In other words, the US is receiving more tariff-free benefits from NAFTA than Mexico. The MFN tariffs are more likely to hinder the US’s exports to Mexico than Mexico’s exports to the US (Table 1). The higher rates would be applied to not only agricultural products; for example, the average tariff for vehicles is as high as 30.2%.

In the Trump Administration, no one understands this very point better than US Agriculture Secretary Sonny Perdue (former Governor of Georgia). Georgia, an agricultural state in the US, has chicken and nuts among its main exports. The average Mexican tariff on poultry meat is as high as 64.1%. Georgia enjoys the significant benefit of NAFTA. Agriculture Secretary Perdue has explained from time to time that a withdrawal from NAFTA does not advantage the US. Mexican Secretary of Foreign Affairs Luis Videgaray Caso seems to understand these facts, saying in August that if the US initiated the withdrawal process, Mexico would walk away from the negotiating table. Instead of making a concession, Mexico has expressed its intention to ignore President Trump’s negotiating tactic.

Contentious Issues in NAFTA Negotiations

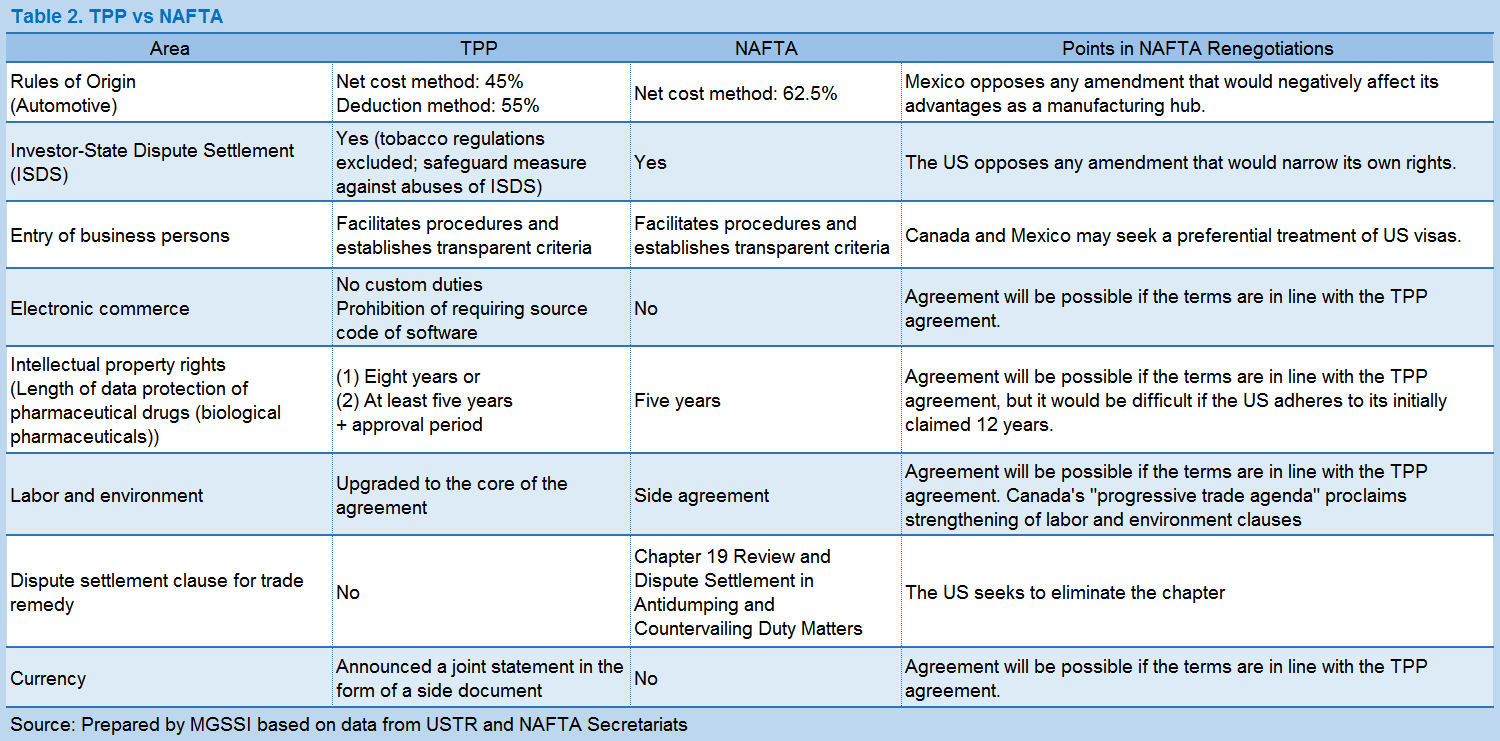

Although it is difficult to predict the outcome of the renegotiations, the TPP agreed by the US, Canada, and Mexico in 2015 provides one criterion. It may be acceptable to the parties if a revised NAFTA does not diverge much from the TPP agreement, simply because that's what once the parties agreed on. Those chapters include “intellectual property rights,” “labor and environment,” “e-commerce,” and “currency” (Table 2). Currency is included in a side agreement to the TPP, instead of the main text. The side agreement entitled "The Joint Declaration of the Macroeconomic Policy Authorities of Trans-Pacific Partnership Countries" confirmed that all TPP countries commit to avoid unfair currency practices and refrain from competitive devaluation. If the US were persistent in incorporating that principle into the legally-binding main text of the agreement, the negotiation would very well face rough going.

If the parties seek more specific agreements for particular chapters than in the TPP, subsequent negotiations will likely have a rocky road ahead, with the rules of origin as a good example. The rules on automobiles are in the spotlight, but the negotiations cover a variety of products, and it is as yet unknown which of them will see compromise from the US and which will not. In the ongoing renegotiations, the parties have already agreed not to negotiate duty-free products. If the US intends to reduce its trade deficits, the amended rules of origin will need to increase the use of US products. However, that idea would not work for products that are unavailable within NAFTA countries. If a threshold for domestic content were raised, companies may give up their efforts to fulfill regional content, and switch to purchase from China or other countries outside the agreement by paying general tariffs. This would raise product costs. At the same time, it only transfers trade deficits from NAFTA to other countries, which is not in line with the US’s negotiating objectives. The rules of origin may be changed without renegotiations or Congressional ratification and governments have tried to amend the rule by consultation.

One of the areas to which Canada and Mexico wish to bring US concessions is “the entry of business visitors.” In particular, Canada is short of skilled labor forces in the areas of 3D printers and AI, and is aiming to facilitate the movement of professionals. Canada may seek a preferential treatment of US visas; however, this issue falls under the Congressional jurisdiction in the US, and the Congress has acknowledged that the issue of movement of people should be dealt with as a part of comprehensive immigration policy. The US negotiators would not respond to such request as the Administration is not granted the negotiating mandate.

The US Political Timetable Towards Ratification

The renegotiating process will not end by concluding the negotiations. In the US, Congress has to pass an implementing bill, thereby bringing the domestic law in conformity with the agreement. The timing of Congressional action largely depends on political environment. Even if the negotiations come to a conclusion, Congress may move after a long interval. The following two schedules and the outcomes give us clues as to when Congress can move ahead with ratification.

The first schedule is about time-consuming procedural obligations between the administration concluding a negotiation and Congress considering the implementing bill, including the Administration’s notification to Congress. If Congress were to amend the bill during the ratification process, a significant discrepancy may arise between what is agreed and what Congress passes. This would force the negotiators to go back to negotiations with its trading partners. For this reason, Congress is not given power to amend the FTA implementing bill and will only vote for or against. The Administration in exchange must follow certain procedures in a transparent manner, including advance notification to Congress of negotiating objectives, and disclosure of the text of the agreement prior to the signing thereof. This system is called the President’s trade promotion authority (TPA), and NAFTA renegotiation is going through the process. More specifically, it requires the Administration to notify Congress 90 days prior to signing the agreement after negotiations are concluded, and the International Trade Commission (ITC) to submit to Congress a report assessing economic impacts of the deal after 105 days of the agreement signed. Therefore, it will take four to six months from the conclusion of negotiations, to the submission of the FTA implementing bill.

Another schedule is that the US midterm elections are scheduled for November 2018. Congress --more specifically, the House of Representatives -- has the authority to submit the NAFTA implementing bill. The new session of Congress beginning in 2019 will reflect the outcome of the elections. Should the Democrats control the House, they would possibly defer submitting the NAFTA implementing bill, or make proposals that would require additional renegotiation, in an attempt to circumvent the Trump Administration’s policy agenda. The midterm ballot shows that if either house turns Democrats, it would be the House of Representatives, rather than the Senate. All the 435 seats in the House are up for reelection, whereas 34 out of 100 Senate seats are up for reelection. Therefore, maintaining a House majority is crucial for the Republican Party.

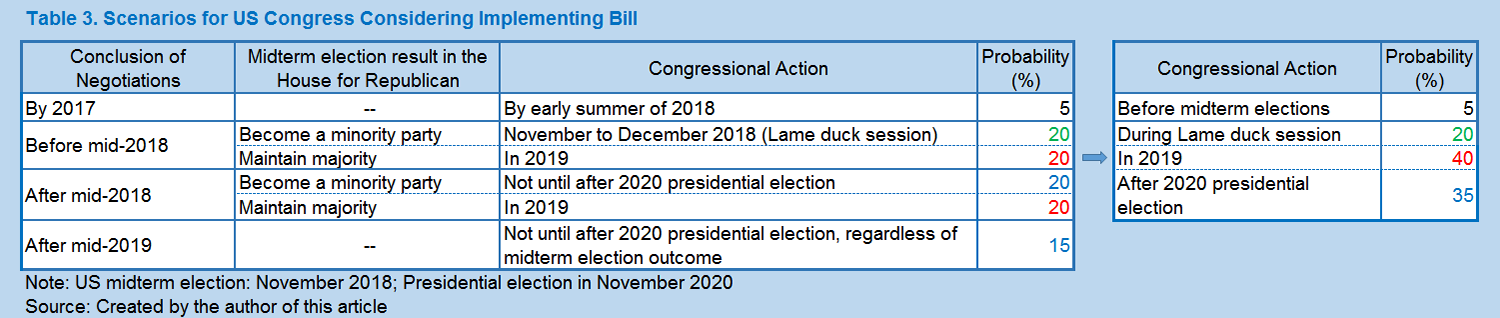

Assuming the six-month interval from the conclusion of negotiations to the submission of the NAFTA implementing bill, the following three ratification scenarios are in the picture.

(1) Fast-track scenario

Passing the implementing bill before the midterm means that should occur no later than the early summer of 2018. As many voters still believe that an FTA leads to jobs losses, Congress is likely to avoid taking a vote on the NAFTA implementing bill before elections. In order to meet the deadline, negotiations should be concluded by 2017. The three countries have tentatively scheduled a target deadline for the end of 2017, but this outlook may well be quite optimistic. Even if the negotiations are concluded by the end of 2017, Congress would show reluctance to ratify the deal by the spring of 2018.

(2) Standard scenario

The next chance for ratification comes after the 2018 midterm elections. A post-election period to the year’s end is called a lame duck session, and Congress remains in session for several weeks. Once the election is over, members of Congress, including ones who lost in the election, can cast a vote without caring much for concerns brought by constituency. Thus, it is possible that controversial bills will be passed in the lame duck session.

If the negotiations reach agreement by mid-2018, it will allow for preparation behind the election campaign and open a path to ratification in the lame duck session. And, if the Republican Party loses in the 2018 midterm elections, it will no longer be able to lead Congress from 2019. This raises the odds that Republican Party tries to consider the FTA bill in the lame duck session. In contrast, if the Party successfully maintains the majority, there is no need to rush: The party may consider the bill sometime in 2019, and the same goes for cases where the negotiations are concluded after mid-2018. As long as the negotiations are concluded by mid-2019, Congress passing the bill by 2019 is possible.

(3) Delay scenario

Ratification will be delayed if the following two conditions are met: 1) negotiations have not reached agreement by mid-2018; and 2) the Republican Party loses in the midterm elections. It is thought that from 2019 a Democrat-controlled Congress will circumvent the Trump Administration's policy agenda by making additional requests. Therefore, Congress is not expected to ratify the agreement during the first term. Another case is that negotiations will be prolonged until after mid-2019, regardless of the outcome of the midterm elections. As presidential primaries will kick off in 2020, Congress is unlikely to consider the bill, although the possibility remains open for ratification in the lame duck session after the presidential election in 2020. Either way, ratification will be delayed until after the presidential election.

Prolonged Renegotiation Obscures Congressional Action

The probability of each scenario can be illustrated in Table 3, based on the author’s own assessment. Although it is difficult to predict the Republican Party’s fate in the midterm elections for the House of Representatives, the cyclical party support shows the Democratic Party leading the poll, and the tailwind for the Republican Party since 2014 is over. At the moment I assumed the two outcomes of Republican's win and loss as equally possible, with a probability of 20% each. From the perspectives of both political schedules and the probability of maintaining a majority party, the best policy for the Trump Administration is to end negotiations by mid-2018. The longer it takes, the more the ratification process becomes subject to the outcome of the midterm elections and the 2020 presidential campaign schedule. If the Trump Administration is aware of these points, it should demonstrate an example of updating an FTA, without adopting a brinkmanship stance of withdrawal.

Note: The original Japanese report was written in October 2017.