Mitsui & Co. Global Strategic Studies Institute

The Globalization Strategy of China ーOutcomes, Challenges, and Opportunities of the “Belt and Road” Initiativeー

Jul. 3, 2017

Hideaki Kishida

Economic Studies Dept.

Mitsui & Co., Ltd. Beijing Office

Main Contents

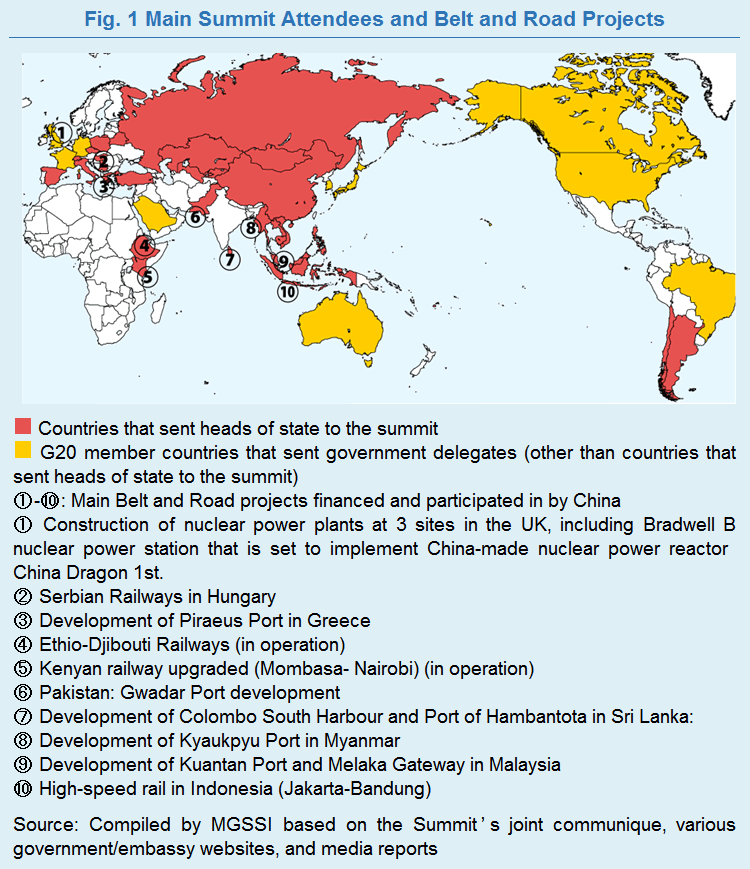

“The world has never been more eager to approach China.” This is an excerpt from a video clip that the Xinhua News Agency released prior to the Belt and Road Forum for International Cooperation (BRF), which was held in Beijing from May 14-15, 2017.1 The summit drew 29 heads of states—more than APEC and G20 did—along with government officials and representatives from several tens of countries, including Japan and the US (Fig. 1). They issued a joint communique pledging to promote the development of the Belt and Road on May 15, and also announced a second forum in 2019.

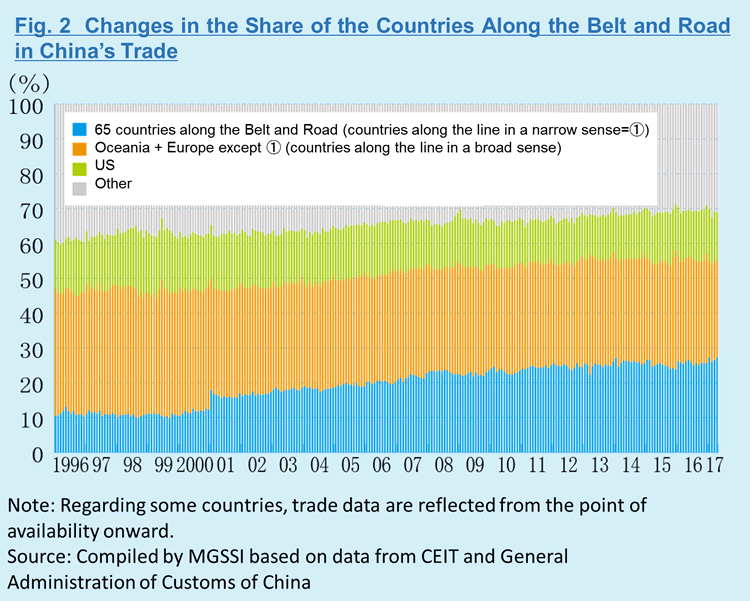

The Goal and Change

The Belt and Road is an initiative that integrates the Silk Road Economic Belt and the 21st Century Maritime Silk Road Initiative, which were respectively introduced by Chinese President Xi Jinping in the fall of 2013. This initiative aims to accelerate policy coordination, infrastructure development and connectivity, promotion of trade and investment, financial cooperation, and cultural exchange in Eurasia, where economic ties have been strengthened in recent years, and thereby to build a seamless, gigantic economic bloc encompassing 65 countries and 4.4 billion people 2 (Fig. 2). China has expanded its market and enhanced its influence (soft power), but at the same time, its Go Global strategy has been criticized as neocolonialism because of issues such as insufficient technology transfer and development of local talent, and environmental destruction. Therefore, the Belt and Road places particular emphasis on the principle of wide consultation, joint contribution, and shared benefits.

The Belt and Road is based on the three pillars: (1) promoting the development of the underdeveloped western part of China; (2) strengthening China’s relationships with high-potential Asian countries; and (3) implementing the “March West” strategy,3 whereby China intends to avoid conflict with the US, which has advocated “Asia-Pacific Rebalance,” while stepping up cooperation with the superpower in other regions. However, some changes have emerged. First, partnerships are expanding geographically under the principle of openness. President Xi had talks with Chilean President Michelle Bachelet in Beijing on May 13, immediately before the opening of the summit, and called on the Chilean President to link the development strategies of the two countries and increase mutual investment under the Belt and Road. The joint communique of the summit emphasized the promotion of partnerships between the Europe and Asia regions (alongside the Belt and Road) and the South America and Africa regions.4 Second, China began to respect existing international rules. The joint communique refers to “fair competition,” “good governance,” “promote peace,” “gender equality,” “economic, social, fiscal, financial and environmental sustainability,” and “respect for intellectual property rights.” None of this language was included in a Belt and Road policy document that the Chinese government published in March 2015.5 Third, the Belt and Road is now more likely to be discussed in the context of anti-protectionism since the Brexit referendum and the US presidential election. The Belt and Road has gone beyond a regional strategy framework and become synonymous with the Xi administration’s globalization strategy.

Outcomes and Challenges

The greatest outcome so far is that China has succeeded in involving numerous countries and companies in the initiative. China had concluded some form of Belt and Road partnership agreement with 68 countries and international institutions as of May 2017 (as announced by the government), and the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB), a symbolic institution of the Belt and Road, has approved the membership of 80 countries and regions as of June. On June 6, China Investment Corporation (CIC), a sovereign wealth fund, held a Belt and Road investment forum in Beijing, and Toyota and Siemens corporate executives were seen among the speakers, most of which were from Chinese enterprises and funds. Hitachi and GE have been making public their expectations of the Belt and Road, and DHL has been rolling out services in line with the Belt and Road (China-Europe land railway transportation). The Infrastructure Financing Facilitation Office (IFFO), which was established by the Hong Kong government in support of the Belt and Road in July 2016, is partnering with not only US and European financial institutions and funds but also three Japanese megabanks. In terms of China–Japan relations, Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe publically made a positive remark on the Belt and Road for the first time on June 5, 20176, and a spokesperson of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of PRC responded by welcoming Japan to the initiative. This suggests the possibility of stepped-up cooperation between the two governments.

Meanwhile, the Belt and Road presents more than a few challenges and risks before the future growth of its centripetal force. First, there is a financing problem. It is unlikely that financial resources will be depleted for China-driven strategic projects, including those for the China–Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC) and the Indonesian high-speed rail (HSR)7, but these projects are not what the Belt and Road is all about. The Asian Development Bank (ADB) estimates that the total infrastructure needs in 44 Asian countries (other than China) over 2016–2030 will be approximately USD 730 billion per year8 , which almost amounts to four years’ worth of China’s current account surplus (USD 196.4 billion in 2016). Although the summit this time promised to boost funds for the Belt and Road through means such as a capital increase for the Silk Road Fund, that amount is rather small in comparison with the overall demand. Zhou Xiaochuan, governor of the People's Bank of China, stressed that "Investment and financing shouldn't be understood as one-way support,” calling for the diversification of financial schemes, such as cooperation among multilateral commercial banks and efficient use of the domestic savings of countries along the Belt and Road. It is understandable that China is taking a cautious stance because of its debt collecting risk in projects already financed9, but if China becomes overly cautious, it may result in weakening the unifying force of the Belt and Road.

Second, there is an international political risk. India refused to send its official delegation to the summit this time, in response to the CPEC passing through the disputed territory between India and Pakistan (northern Kashmir). India’s Ministry of External Affairs on May 13 issued the statement that “No country can accept a project that ignores its core concerns on sovereignty and territorial integrity.” In addition, moves by the Chinese People's Liberation Army (PLA) are crucial. It is unclear how communication and cooperation are being carried out between the Army, which leads China’s maritime advance, and the authorities in charge of the Belt and Road (the Ministry of External Affairs, the Ministry of Commerce, etc.). If the Army were to move abruptly in the South China Sea and the Indian Ocean and strongly provoke countries concerned, the existing Belt and Road cooperation would fail. At the summit, President Xi reiterated, “(In the construction of the Belt and Road) we won’t set a political agenda. It’s not exclusive.” However, the truth is that China did not invite Taiwan, while welcoming a delegate of 30 people from Hong Kong. South Korea also did not receive an invitation from China until after its presidential election (May 9), as the relationship between the two countries soured over the Terminal High Altitude Area Defense (THAAD) system. These moves by China are definitely political. On the other hand, Latvia’s cabinet expressed its willingness to have trilateral talks and a cooperative framework among Latvia, China, and Russia, which implied Latvia’s intention to use China as a counterbalancing force to Russia. Other BRI partners also have their respective political motives. If China failed to properly control the Army and respond to international political risks, the stable development of the Belt and Road would be at stake.

Lastly, there is a domestic problem. One point to be noted is China’s commitment to reforms. China and the EU signed a memorandum of understanding on Belt and Road cooperation, and they are on the same page in their anti-protectionist stance. However, against China’s wishes, the EU has refused to acknowledge China as a market economy country, claiming that the Chinese government’s support for its iron and steel industries is protectionist. The summit’s joint communique touts opposition to all forms of protectionism. If China were unable to demonstrate that while accelerating its domestic reforms, the momentum of the Belt and Road would be lost by the advocate itself. The second point is the people’s support. While the Chinese media is fueling the Belt and Road boom, some experts at government-run research institutions, as well as local government officials, are directing a suspicious look at the economic effect of the Belt and Road. Chinese citizens do not have much interest in this initiative in the first place. They will not see it as a problem as long as they are not so interested, but if the country’s domestic economy and fiscal conditions turned for the worse, dissatisfaction with the Belt and Road might spread throughout the Chinese citizens, and such frustration is likely to connect with a power struggle. As rumor has it that a new command organization for the Belt and Road will be formed at the National Congress of the Communist Party of China (NCCPC) in the fall of this year, the government is being challenged over its political skills in continuing to expand its domestic support for many years to come.

Expanding Opportunities

The Belt and Road initiative, albeit still immature and unclear, can be recognized as having a certain amount of potential, based on its inclusiveness and scale, China’s economic power and aggressive participation, and network expansion so far. Meanwhile, what is the mindset of Japanese companies? According to a survey conducted by Thomson Reuters in May, 95% of companies responded that they do not wish to participate in Belt and Road projects.10 All the questions were regarding infrastructure investment, but yet their responses appeared to be quite negative about the initiative. However, the Belt and Road is also rather pluralistic. In addition to the development of infrastructure, such as roads and railways, leading Chinese manufacturers (Beijing Automobile Works, Huawei Technologies, etc.) and IT service giants (Alibaba, Tencent, etc.) are expanding to countries along the Belt and Road, where industrial parks and cities are being constructed to invite such companies. Furthermore, various moves are taking place simultaneously, including swap agreements between Chinese yuan and the currencies of the countries along the Belt and Road to make yuan an international currency, network expansion for direct transactions, and FTA negotiations, among others. It is not that all the projects are proceeding at a steady pace. While some of them are already complete, some other efforts are currently underway, and such progress will also contribute to developing some countries and regions. As a result, there may be new moves of goods, money, and services between China and the countries along the Belt and Road, or between countries along the Belt and Road. Japanese companies need to observe the overall situation, including the challenges and risks mentioned above, while eying individual countries and policies as well as moves by Chinese companies and the like.11 Then they will study approaches to explore new business and take timely action. Macro and micro perspectives and flexible response will be the key to tapping into the growing opportunities brought by the Belt and Road.

- 世界舞台上的习近平-新华网

- Figures reported by Xinhua News Agency, among others. They seems to include Japan, South Korea, North Korea, Taiwan, and Eurasian countries other than some in Europe (Western and Northern Europe, etc.).

- October 2012 Wang Ji Si (王缉思): “西进”,中国地缘战略的再平衡 (“March West,” Rebalancing China’s Geostrategy)

- North America was not mentioned, presumably because no North American leaders were dispatched to the summit.

- 推动共建丝绸之路经济带和21世纪海上丝绸之路的愿景与行动

- Prime Minister Abe spoke at the dinner of the International Conference on The Future of Asia, stating that the Belt and Road initiative has the potential to connect the East and the West across the ocean and a diversity of regions in between. However, he also requested that the projects should be economically efficient, that loans must be repayable for countries in which infrastructure is developed, and that maintaining financial health is essential.

- The CPEC is a transport route for energy, etc., without crossing the Malacca Straits; China’s first export of high-speed rail technology is destined for high-speed rail in Indonesia.

- February 2017 ADB “Meeting Asia's Infrastructure Needs” figures include costs for responding to climate change issues.

- For example, the Financial Times (FT) in May 2016 reported that as a “private forecast” of Chinese officials, China would be unable to recover 30% of its investment in central Asia, 50% in Myanmar, and 80% in Pakistan. James Kynge, “How the Silk Road Plans Will Be Financed” May 9, 2016

- Mary 25, 2017 Reuters Corporate Survey: Japan Inc. sees better opportunities beyond China's “Belt and Road”

- In China, there are many companies and funds seeking business partners for efficient development of projects, as well as risk hedge and other reasons.