Mitsui & Co. Global Strategic Studies Institute

Thailand’s Ambition to Become a “High-income Nation” -- Political Unrest and China’s Growing Influence

Dec. 9, 2016

Tomoko Ebine

Asia, China & Oceania Dept.

Mitsui Global Strategic Studies Institute

Main Contents

As part of Japanese companies’ Thailand-Plus-One strategy1 in ASEAN, Thailand is taking the leading role in a gigantic supply chain in the Greater Mekong Subregion that brings together neighboring Cambodia, Laos, Myanmar, and Vietnam (CLMV). Japanese companies made inroads into Thailand in the early days of foreign investment. A typical example of this is Japanese automakers and parts suppliers, who built local production bases in response to the Thai government’s investment incentives for the automotive industry in 1960, and today their production capacity has reached 3 million units a year. In ASEAN, no other country has been able to consolidate manufacturing and supplier bases, typically the automotive industry, like Thailand, which can now boast of being the biggest manufacturing hub in the region.

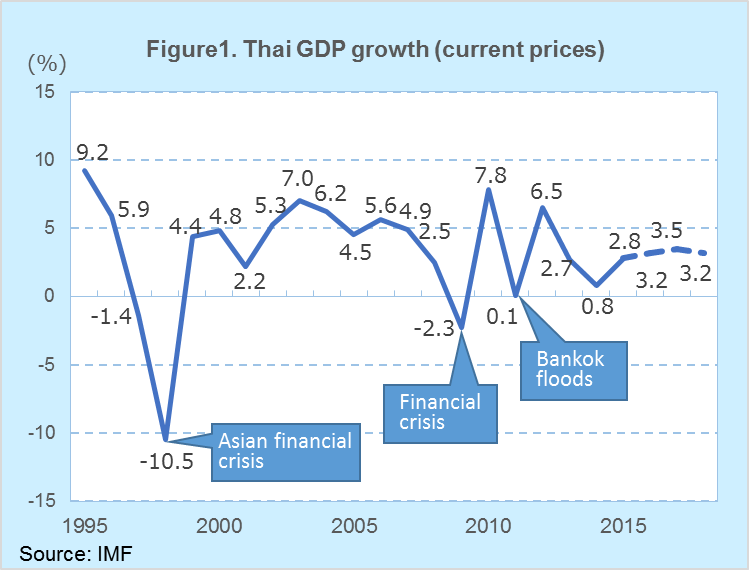

In recent years, however, the Thai economy has been going through hard times (Figure 1) due to weak crop prices, rice in particular, drought, and, notably, China’s economic slowdown, despite the former Yingluck Shinawatra administration’s economic package of first car scheme (tax refund for first-time car buyers) and an increase in the minimum wage (300 baht2 per day nationwide). US Moody’s pointed out last year that Thailand’s structural problems were attributed to its ‘losing competitiveness’ and ‘political instability’. The natio3n is indeed facing hardship both politically and economically.

THE NATION’S STRUCTURAL PROBLEMS AND POLICIES UNDER MILITARY REGIME

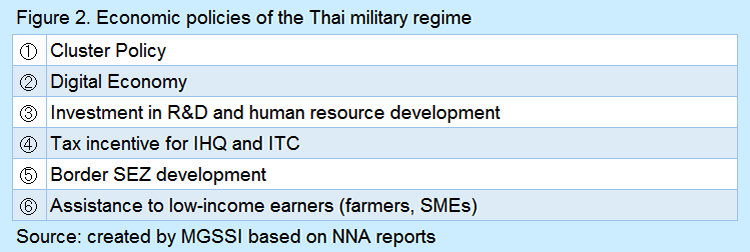

Taking on the enormous aftermath of the former administration’s misguided policies, such as huge losses caused by the rice mortgage scheme, Prime Minister Prayuth Chan-ocha named Mr. Somkid, the current deputy prime minister and the former finance minister under the Thaksin regime, to lead the new economic team in the cabinet reshuffle in August 2015. The Prayuth administration has been committed to full-fledged economic recovery and expansion of export centered on “enhancing its economic level” and “raising its global competitiveness” (Figure 2).

(1)Transition to a High-income Nation by 2026 and Economic Stimulus Measures

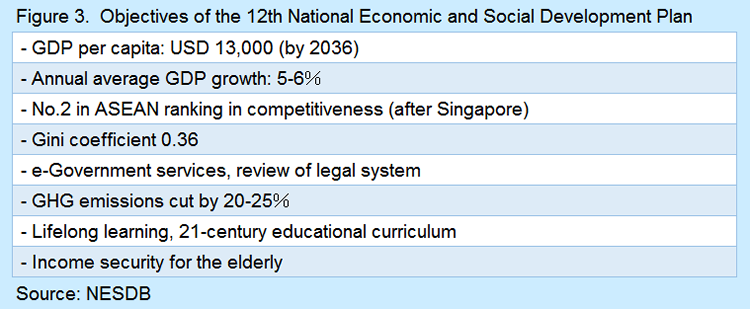

In July 2016, the National Economic and Social Development Board (NESDB) set forth the five-year development plan of the 12th National Economic and Social Development Plan (2017-21), which aimed at achieving both an average of 5 to 6% GDP growth a year and average personal income from the current USD 6,000 to 13,000 by 2036 (Figure 3), so as to transition to a high-income nation3 as defined by the World Bank by 2026. Thailand is already deemed as an upper-middle income economy, but large economic disparities are apparent between Metropolitan Bangkok and the rest of the country; the average personal income of the former (Bangkok and the neighboring six provinces) exceeded USD 10,000, while the latter was USD 3,121 as of 2013. Also, in order to recover from the continued recession, the Thai government is slated to stimulate the economy, especially low-income farmers and small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs), by means of the rice pricing scheme, subsidies to farmers and the low-interest loan programs to SMEs. To the military junta, offering economic assistance to rural areas with Thaksin constituencies is inevitable to ensure social stability as well as attract potential voters.

(2) Increasing Global Competitiveness and Reducing Inequality

Thailand has been going through chronic labor shortages in recent years, raising its labor cost4. Plus, fast-growing neighbors like Vietnam are trying to catch up with Thailand, threatening its competitive edge. To avert the middle income trap5 and transform to a high-income nation, it is pursuing structural reforms such as shifting from labor-intensive to high-tech industries or industries with higher added value.

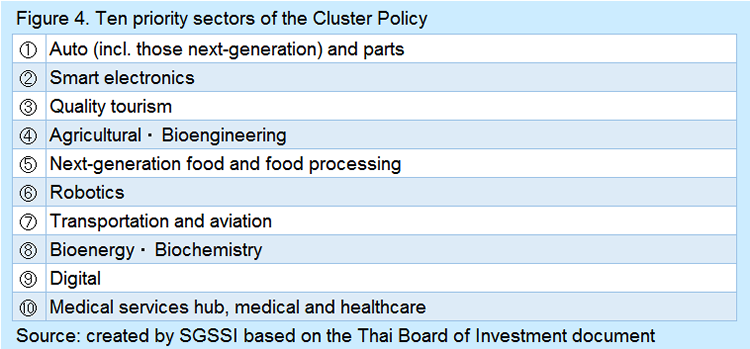

To promote this, the Cluster-based Special Economic Development Zones Policy (Cluster Policy) was announced in September 2015. The government specified the ten priority business sectors (Figure 4) and regions that are to be developed to intensively enhance competitiveness. Investment in R&D and human resource development is of the highest importance and a prerequisite for various incentives. The Ministry of Digital Economy and Society was newly created in September 2016, and a total budget of 280 million baht has been allocated for digital economy projects, such as smart city development and support for the software industry. The agency is also building legal infrastructure for fin-tech business.

Moreover, with the aim of narrowing the economic gap between urban and rural areas and also eliminating labor shortages, Thailand is promoting SEZs in its border regions. These border SEZs are expected not only to develop remote areas but also to encourage business tie-ups with the neighboring CLM economies under the Thailand-Plus-One strategy, so that the economy of the whole Mekong region can be enhanced. Industrial advancement and rural development are the tandem of economic measures of the Prayuth administration.

(3)Hub of ASEAN – Attracting Regional Headquarters

Based on ASEAN, a community with free cross-border movement of people, goods, and capital, Thailand intends not only to become a manufacturing hub of the region but also to attract regional headquarters of foreign companies for trade, financial transaction, and human resource development. To that end, the Thai Board of Investment introduced two tax incentive measures for international headquarters (IHQ) and international trading centers (ITC) in January 2015. Just like Singapore, the hub of the regional headquarters of many organizations, Thailand aspires to be another hub in ASEAN. As Thailand boasts lower costs, including labor, than Singapore, as well as an established manufacturing hub, foreign companies, manufacturers in particular, are setting up regional headquarters in Thailand for particular business functions that they deem optimal to locate there; this can be called the “Singapore-Plus-One” movement.

ROYAL SUCCESSION AND POLITICAL UNREST

Prayuth’s economic reforms, nevertheless, will never be an easy way out. His administration took power in a military coup (May 22, 2014) after the former Prime Minister Yingluck Shinawatra was impeached amid intense conflict between pro- and anti- Thaksin protesters since late 2013. After assuming power, Prayuth ousted the Thaksin clan from positions of authority. As a result of the constitutional referendum in August 2016, the military junta received approval to remain in power virtually for the next five years, while the nation is expected to go along the roadmap of democracy via the general election to be held this year end. However, the death of the King Bhumibol, who reigned over 70 years until October 13, 2016, is feared to blur Prayuth’s blueprint.

Chosen by his father the late king, Vajiralongkorn took the throne last December. Before his accession, however, the royal family, the army, and the Thai public were intricately split; Queen Sirikit, the Royal Thai Police, and the Thaksin supporters backed Vajiralongkorn, whereas Privy Council President Prem and the army supported Princess Sirindhorn6, who is highly popular with the public. Since the late king had long acted as a mediator in recurring conflicts in Thai politics, he had been implicitly deemed as the justification for the military governments thus far, and this allowed stricter information controls relating to lese-majesty. Resulting from those unresolved conflicts, highly uncertain situations are likely to continue in Thailand. Social unrest will definitely affect tourism as well as private consumption. The stagnant economy will reignite conflicts between the Thaksin clan and the opposition and also between urban and rural residents over economic inequality, thus further extending uncertain situations. More time will be needed until fundamental issues for this country can be solved.

EXTERNAL PRESSURE ON ECONOMIC STRUCTURE – CHINA’S EXPANSIVE FOOTPRINT

In Thailand, despite repeated coups over the past half a century, no major change has been made in the direction of its economic policy. Under a rigid bureaucracy, the next administration is likely to carry on with the current policy of attracting foreign capital. In order to change its industrial structure and become a high-income nation, Thailand definitely needs investment and assistance from foreign countries. China is now the biggest trading partner for Thailand after it superseded Japan in 2013, although Japan still retains first place in investment and financing, including FDI by Japanese manufacturing businesses operating in Thailand and overseas development assistance (ODA) programs. This means that Japan could be a key player in transforming Thailand’s industrial structure. In fact, many Thai industrial complexes were designed taking into account the location of local Japanese subsidiaries, and around half of the 100 or so applications for the aforementioned IHQ scheme were made by Japanese companies.

Critical of military rule, the US and the EU are tending to reduce trade and investment in Thailand, and this will, in contrast, help China make an expansive footprint. Indeed, traces of “China money” can be found here and there in Thailand as well as neighboring countries, as in joint infrastructure projects such as the railroad from Bangkok, via Laos, to Yunnan, China. Thailand must have been thrilled by the recent offer from Alibaba, a Chinese e-commerce giant. Its Executive Chairman, Jack Ma, announced last autumn that his company planned to provide e-commerce and financial services platforms to encourage exports by Thai farmers and SMEs, which is eventually likely to boost the rural economy of Thailand. That said, as long as Thailand depends on foreign investment, its economy will remain at risk from the global economy, particularly China and Japan. In addition, with its inherent problems of economic inequality and political unrest, Thailand has a long way to go before attaining its goal of becoming a high-income nation.

- Business strategy adopted by many Japanese manufacturing companies in recent years to relocate their labor-intensive manufacturing functions from Thailand to neighboring Cambodia, Laos, Myanmar, and the border SEZs adjoining Myanmar.

- 1 Thai baht = approx. 3.06 yen (as of November 15, 2016)

- Nation/region with gross national income (GNI) per capita above USD 12,746 as of 2013.

- For example, the average monthly wage of urban blue-collar workers is USD 162 in Cambodia (Phnom Penh) and USD 127 in Myanmar (Yangon), way below Thailand’s (Bangkok) USD 344 (source: JETRO, comparison of investment cost)

- A concept the World Bank introduced in An East Asian Renaissance (2007); the situation in which a middle-income country’s growth slows after reaching middle-income levels by making use of labor-intensive or resource-dependent industries. Its transition to high-income levels then seemingly becomes unattainable if it fails to strive for technology innovation, industrial diversification and upgrading, and human resource development.

- King Bhumibol added Princess Sirindhorn to those with the right of succession to the throne in 1978, which made her second-in-line to the throne (after Vajiralongkorn).