Mitsui & Co. Global Strategic Studies Institute

Challenges Facing Sub-Saharan Africa, and Japan

Oct. 5, 2016

Keiichi Shirato

Middle East & Africa Dept.

Mitsui Global Strategic Studies Institute

Main Contents

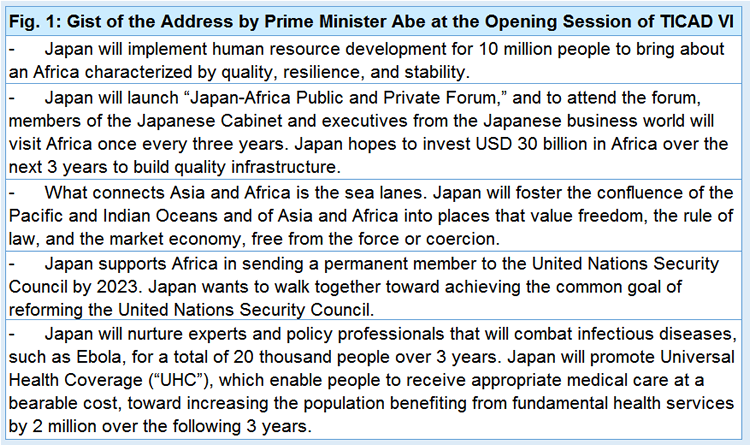

The sixth Tokyo International Conference on African Development (“TICAD”) (TICAD VI) was held in the Kenyan capital of Nairobi on August 27-28, 2016, and hosted by the Japanese government, where Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe pledged to make an investment in Africa worth USD 30 billion in total (investments from private and public sectors combined) over the next three years (Fig. 1). TICAD, which was first held in 1993, had been held every five years up until TICAD V in 2013. From this year, however, the interval of the conference was shortened to three years, since the pace of African economic development has accelerated. This year marks the first year that TICAD has been held on African soil.

In Sub-Saharan Africa, which consists of 48 countries in the region lying south of the Sahara Desert, the UK and France were previously colonial powers. In the past, these two countries used to have large economic interests in this region. In recent years, however, various countries across the world have been bolstering their efforts to encourage their country’s corporations to expand business in the region. This report provides an overview of the efforts made by such countries, and also examines Japan’s approach, in light of the challenges facing Sub-Saharan African countries.

Population increase, an urgent issue to be addressed

Approximately 60% of the Sub-Saharan Africa’s GDP originates from the oil industry. As such, a fall in crude oil prices casts a huge negative impact on the region’s economy. According to the IMF, the real GDP growth rate of Sub-Saharan Africa in 2016 is expected to fall to 1.6%. Although growth rate in the range from 6 to 8-plus % is expected to continue for some countries in the region, the economic growth of the entire Sub-Saharan Africa is slowing down compared to the decade from 2003 to 2012, when the region’s average annual growth rate marked 5.9%.

Amid this situation, Sub-Saharan Africa’s population has been increasing at the rate of 2.6-2.7% per annum, the world’s fastest pace by region. The UN estimates that the population in the region, which was approximately 962 million in 2015, will increase to approximately 2.1 billion by 2050, which, at that time, will represent approximately one fifth of the entire population of the world.

Stable job and food supply is indispensable in linking population increase to production increase. Although development of the manufacturing industry is essential for job supply, in Sub-Saharan Africa, the manufacturing industry accounts for only about 10% of the region’s total GDP. Even in South Africa, which boasts the most developed manufacturing industry in the region, the unemployment rate exceeds 25%.

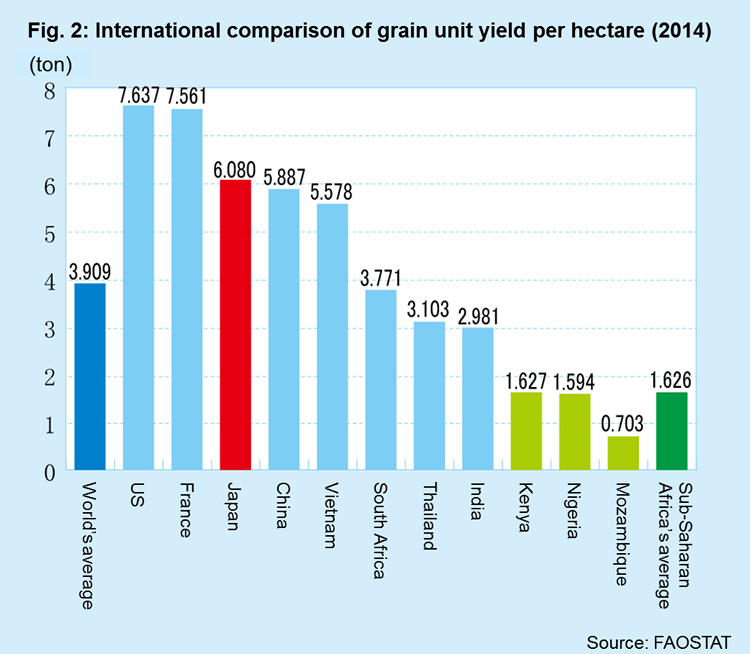

Now, let us turn our attention toward the food issue. The grain unit yield per hectare in Sub-Saharan Africa remains at about 1.63 tons, lagging far behind the world’s average (which is 3.91 tons), due to the insufficient penetration of irrigation systems and use of chemical fertilizers (Fig. 2). Despite the fact that about 60% of the total work force in Sub-Saharan Africa is engaged in agriculture, the region imports much of its staple cereal grain. The slowdown of the economy, triggered by the falling prices of natural resources, once again highlights the challenges facing Sub-Saharan African countries, namely, diversification of industries and modernization of agriculture.

Countries Targeting African Markets

With a view to breaking off from the vulnerable industrial structure described above, a move to foster the manufacturing industry and modernize agriculture is gaining momentum in Sub-Saharan African countries. Meanwhile, major countries in the world have also taken notice of the future potential of the markets in Africa with an ever-growing population. Accordingly, these countries are building aid frameworks for Africa, thereby promoting the business expansion of their nations’ corporations on African soil.

For example, China, Africa’s biggest trading partner, used to promote investment in the continent mostly in the field of resources. However, it shifted its investment focus to the fields of railroads, power stations, and ports in around 2012, and recently, is actively initiating the transfer of its manufacturing industry to Africa. The Chinese government also announced aid programs for Africa worth USD 60 billion, together with the ten priority fields, which include industrialization and agriculture modernisation, at the sixth Forum on China–Africa Cooperation (“FOCAC”) (which has been held every three years since 2000) convened in December 2015. China’s aid for industrialization is part of its new strategy called the “international cooperation in production capacity,” whereby production facilities used in such manufacturing industry sectors as iron and steel, cement, and glass are exported to developing countries. China’s domestic political motive to transfer its over-production capacity overseas can be seen here in its ostensible efforts to meet Africa’s needs.

In the case of India, the government has strengthened its relationship with Africa by holding the India–Africa Forum Summit (“IAFS”) three times in total so far (in 2008, 2011, and 2015). At the IAFS III held in 2015, Indian Prime Minister Modi announced a foreign aid package for Africa, including a credit accommodation worth USD 10 billion over five years as well as complimentary aid programs worth USD 600 million in fields such as healthcare India, previously a British colony, has strong connections with African countries that were likewise colonized by the UK, and, over 2.7 million people of Indian descent inhabit Africa. Some of them hold an important position in the local business world in countries such as Kenya and Tanzania. The Indian government is aiming to expand Indian companies’ business in Africa by utilizing these connections as a foothold. There is a high possibility that India will become a major player in the development of Africa, along with the former colonial powers such as the UK and France, and China.

In the US, the African Growth and Opportunity Act (“AGOA”) came into force in 2000, under which African products have been imported without being subject to tariffs. However, the US did not think strongly of promoting business expansion of American companies in Africa, and its attention concerning Africa was largely placed on security issues, with a primary focus on anti-terrorism measures. In June 2013, however, President Obama unveiled the “Power Africa” project, which seeks to double the electricity penetration rate in the continent, and thereunder, he pledged a foreign aid package and an investment, worth USD 7 billion and USD 9 billion, respectively. Thereafter, in August 2014, the US hosted for the first time the United States–Africa Leaders Summit, where the leaders of African countries were invited to Washington D.C. It is not clear, however, whether the US will hold such conference again, unlike Japan, China, and India, which regularly organize summit meetings with African countries.

Challenges Facing Japan

TICAD initially started out as a policy forum where the paradigm of the development of Africa was discussed with a focus on the arguments pertaining to development aid. Following the African economy’s growth, however, the Japanese government announced its intention to strengthen public-private initiatives at TICAD IV in 2008, and has continued with this stance, whereby it supports investment in Africa by private sector. Then, at TICAD V in 2013, the Yokohama Declaration 2013, which pursues promotion of private sector-led growth, was adopted, marking a significant transition in the policy tools of Japan’s diplomacy concerning Africa, namely, from aid to investment.

At TICAD VI of this year, in addition to adhering to the line of the private sector-led growth, a policy that aims to differentiate Japan from China was distinctly mapped out. The Nairobi Declaration, which was adopted at this year’s meeting, lists the “three major emerging challenges in Africa;” namely, (i) the decline of global commodity prices, (ii) the Ebola outbreak, and (iii) radicalization, terrorism, armed conflict, and climate change. Also, Japan’s aid for economic diversification was stipulated in the declaration, in order to address these issues, which attests to Japan’s readiness to respond to the needs of African countries that wish to receive aid for the fostering of their respective manufacturing industries and agricultural modernization.

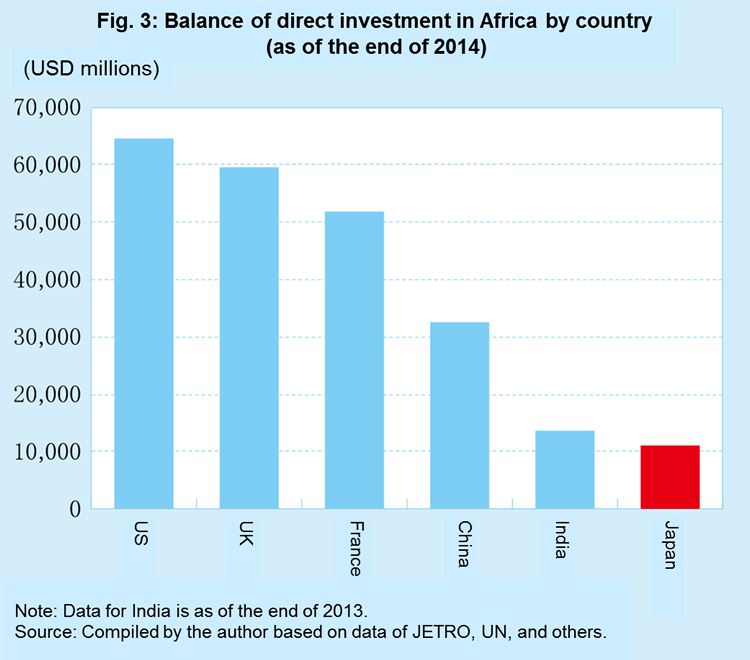

Furthermore, as a highlight of the concrete measures of Japan’s said stance, a policy to promote investment in “quality infrastructure” was also stipulated. While the balance of Japan’s investment in Africa as of the end of 2014 was approximately USD 10 billion, that of India and China was estimated to be approximately USD 13.6 billion and USD 32.5 billion, respectively. In the case of the US, the UK, and France, that same figure exceeds USD 50 billion (Fig. 3). Also, not only in terms of the size of the investment in Africa, but also in terms of cost competitiveness, Japanese infrastructure programs have a disadvantage compared with the Chinese and Indian ones. The emphasis on “quality” is likely a result of an attempt to differentiate Japan from China, in particular, by stressing that Japan’s sophisticated technologies will contribute to solving the challenges facing Africa.

Business opportunities where Japanese quality infrastructure facilities (such as environment-friendly power stations, and equipment for waste disposal required as a result of urbanization) are likely able to make a strong showing, do exist in Africa. At the same time, however, “high quality,” in most cases, conversely means “high cost”, and accordingly, quality infrastructure facilities are not necessarily welcomed in Sub-Saharan Africa. Quality infrastructure is a double-edged sword in Africa, a place where intense international competition is emerging.

Regarding Japan’s aid programs announced at TICAD VI, generally positive responses have been heard from African countries. However, attention should be paid to the candid remarks of Rwandan President Paul Kagame made during an interview with NHK held on the sidelines of TICAD VI, indicating his view that Japan seems to be hesitating to increase investments in, and strengthen cooperation with, Africa. While a spate of investments is flowing into Africa from all over the world, Japanese major companies’ slowness in getting started is also known in Africa. It cannot be denied that the African elite generally hold the perception of Japanese companies that management is reluctant to take risk, and decision-making is slow, while at the same time appreciating their preciseness in their work and sophisticated technology.

In some parts of Africa, activities of Islamic militant groups have been witnessed. Also, there are countries that are not safe, or where corruption of government officials is rife. Hence, it is most likely true that doing business in Africa is comparatively difficult. However, Executive Vice President Katsumi Hirano of the Institute of Developing Economies, Japan External Trade Organization points out that companies of other countries are not vacillating as a consequence of such difficulties, and that this suggests that Japanese companies’ slowness in starting out in Africa is a problem lying with the Japanese companies, not Africa. In today’s world, where companies from across the world are targeting African markets, whether Japanese companies can successfully enter them may well serve as a barometer indicating Japanese companies’ ability to compete on the global stage.