Mitsui & Co. Global Strategic Studies Institute

Considering the Effects of Japanese Sanctions Against Russia

Jul. 7, 2016

Daisuke Kitade

Europe & CIS Dept. Mitsui Global Strategic Studies Institute

Main Contents

What are sanctions?

Sanctions are generally viewed as a diplomatic tool designed to induce a change in policy by obstructing trade, investment, and other economic activity of the targeted party to persuade it to calculate the cost effectiveness of that policy. In his 1967 analysis using the example of the UN sanctions against Rhodesia, Galtung suggests that a government designated as the target of sanctions is, in fact, strengthened by the sanctions because it adapts to the situation through import substitution and similar measures, and because the country’s citizens are willing to close ranks in response to the external threat (the “rally round the flag effect”), and he claims that schemes to achieve a political outcome through economic costs are “naïve” and that sanctions have no effect whatsoever1. This claim has been repeated in the discussions surrounding sanctions against Russia with which this report is concerned, and since Gaddy and Ickes of the US Brookings Institution have also repeated Galtung’s claim of 50 years ago, it can be said that it is still the tendency today to consider that changing the policy of the target is the criterion to evaluate success or failure of sanctions.2

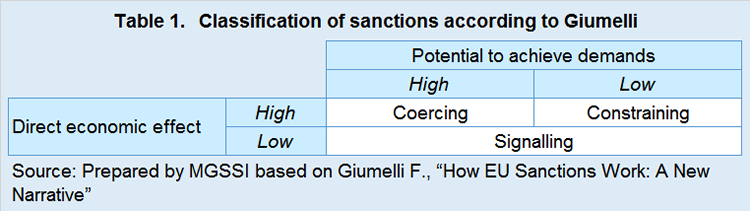

However, in recent years, a different view has been expressed that the objective of sanctions is not solely to bring about a change in the policy of the target. An especially clear-cut example of this is sanctions against terrorist organizations. It is clear that you cannot expect to change the behavior of an extremist organization by imposing sanctions when the very raison d’etre of that organization lies in performing acts of terror. Sanctions against terrorist organizations are designed to limit their capacity to commit acts of terror by obstructing the source of weapons and funds through means such as arms embargoes and asset freeze, in other words, “constraining” sanctions. With constraining sanctions, it is usually the case that the demands of the sanctions is infeasible for the targets to comply with, such as stopping acts of terror or, as in the case of US sanctions against Cuba, the resignation of the government, or that demands are not specified at all. On the other hand, with “coercing” sanctions that seek to prompt a change in policy, specific achievable demands are expressed, such as the release of hostages or the holding of democratic elections. In addition, it is also possible to envisage sanctions that do not impose an economic cost on the target. Sanctions of this kind are “signalling” sanctions that send a message, such as opposition to the target’s policy, both to the target and to the international community. Giumelli classifies sanctions into three types, as shown in Table 13. To consider the effects of sanctions, the type of sanctions should be identified and the effects determined on the basis of whether that objective has been achieved. This classification of sanctions into coercing, constraining, and signalling has also been introduced into the Guidance on financial sanctions published by HM Treasury of the UK in April 20164, and the objective of this report is to consider the effects of the sanctions against Russia using this logical framework.

Japanese sanctions against Russia and their evaluation

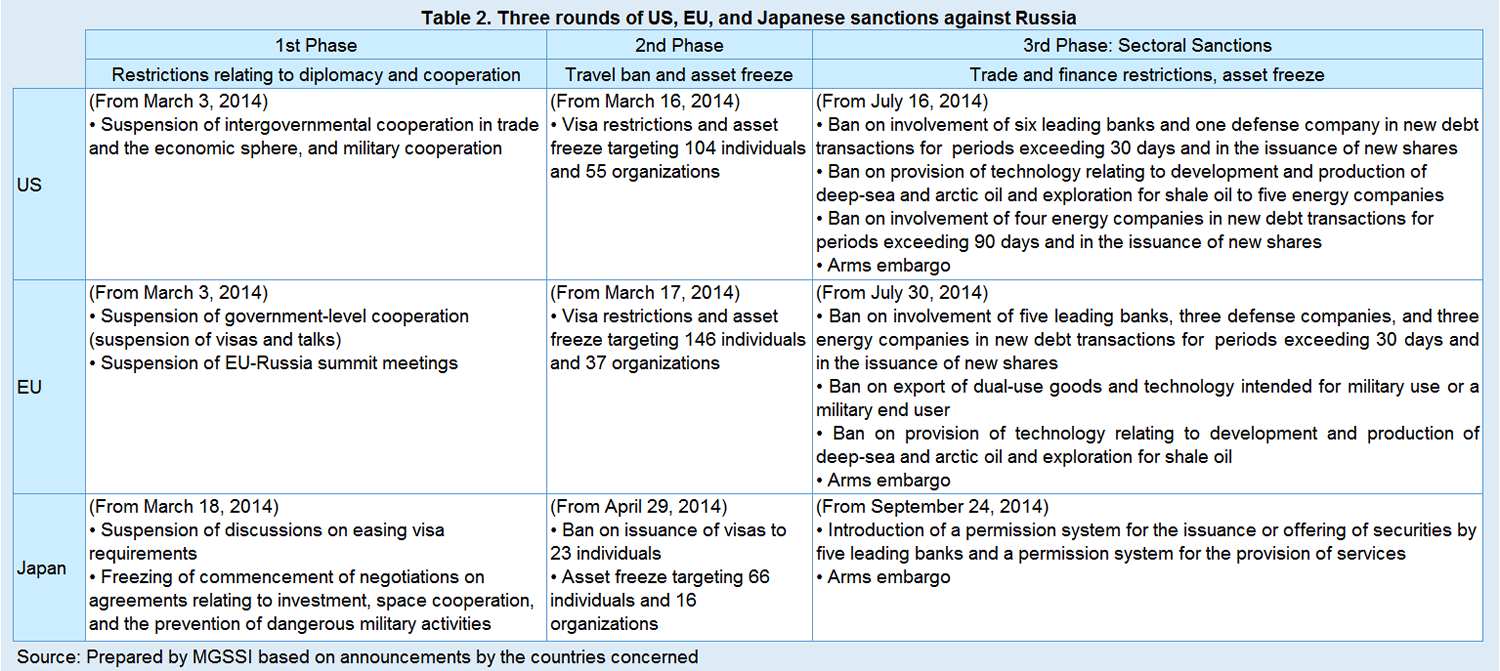

Up to now, sanctions against Russia have been imposed in three phases in accordance with the evolving situation in Ukraine (Table 2). In the first phase, diplomatic sanctions were imposed on Russia in response to its military intervention in Ukraine in late February 2014. On March 3 of the same year, the G7 decided to halt preparations for the Sochi Summit, which was scheduled to take place on June 4 and 5. It was on March 18, following the holding of a referendum in Crimea, that Japan announced its own diplomatic measures against Russia, consisting of suspending talks related to easing visa requirements and freezing commencement of negotiations on agreements relating to new investment, space cooperation, and the prevention of dangerous military activities. Since these Japanese sanctions are not accompanied by any significant economic cost for Russia, they are signalling sanctions. In addition to sending a message that Japan does not recognize the Crimean referendum and opposes Russia’s annexation of Crimea, Japan’s minister for foreign affairs announced that, “Japan will never overlook any attempt to change the status quo by force.” These measures can be taken as a warning message to countries that might wish to follow Russia’s example and attempt to change the status quo by force. Since Japan’s message was duly broadcast to Russia and the international community, round one of Japanese sanctions can be judged a success.

A second phase of sanctions against Russia, consisting of a travel ban and asset freeze against individuals and organizations was implemented at an early stage, on March 16 to 17, by the US and the EU, and it is also targeting members of President Putin’s inner circle, while it was not until April 29 that Japan imposed its second batch of sanctions. The Japanese sanctions were limited to a ban on the issuing of visas, which was not accompanied by an asset freeze, and the names of the people targeted by the measure were not announced. Since these sanctions do not impose an economic cost on Russia, they are typical signalling sanctions. As Cortlight and Lopez have pointed out5, it is common practice when introducing a travel ban to accompany it with financial sanctions to increase the pressure on the target, and Japan’s decision to limit sanctions to a travel ban is considered to be deliberate. Furthermore, it is also considered deliberate that Japan imposed sanctions on Russia at a later date than the US and the EU, and it didn’t disclose the names of the persons targeted. On August 5, when the US and the EU had already imposed sectoral sanctions on Russia, Japan announced the imposition of additional sanctions, freezing the assets of 66 individuals and 16 organizations. However, these sanctions were limited to persons involved in Crimea and separatists in Eastern Ukraine, and these, too, have a limited economic cost.

The primary recipients of the message sent by Japanese sanctions against Russia are the US and the EU, which have also imposed sanctions on Russia, and the international community. It can be seen as a statement of Japan’s intention to maintain good relations by showing its willingness to cooperate with its Western allies in maintaining the international order, and a demonstration of its opposition to changing the status quo by force. The secondary recipient is Russia. Along with the message that Russia’s annexation of Crimea and destabilization of Eastern Ukraine are not acceptable to Japan, the fact that the sanctions against Russia were intentionally limited, as described above, can be seen as sending the message that Japan does not intend to damage Russia economically, and that it views Russia as important. While Russia also imposed retaliatory sanctions on Japan, since it did so in August, the measures were limited to a travel ban, and the names of the targeted persons were not announced, it was a symmetrical response to the Japanese measures. In addition, although Russia has introduced a retaliatory import ban on agricultural products from countries that have imposed sanctions on Russia, the fact that Japan has not been designated as a target of the embargo suggests that Russia fully understands the message contained in Japan’s sanctions against it. Thus, phase two of Japan’s sanctions against Russia can be rated a success.

In a third phase of sectoral sanctions, the US and the EU announced (1) a 30-day limit on the period for which major Russian banks can raise loans, (2) a ban on the provision of technology and services relating to drilling for deep-sea and arctic oil and shale oil, and (3) a 30-day limit on the period for which a Russian defense company can raise loans, and an arms embargo. It is the financial sanctions in measure (1) that places a large, short-term economic cost on Russia. In addition, because it was deemed that an embargo on Russian oil would benefit Russia due to the resulting rise in the price of oil, measures that will affect Russia’s oil production in the medium to long term have been implemented. Sectoral sanctions were imposed by Japan on September 24, and they consisted of an arms embargo, curbs on the issuing of securities by five leading Russian banks, and restrictions on the provision of services relating to the issuing of securities. Since Japan does not export weapons to Russia, and it is hard to imagine that leading Russian banks would raise large amounts of financing in Japan’s securities markets, these Japanese sanctions clearly do not impose any economic cost on Russia. Japan’s sectoral sanctions are also of the signalling variety and the principal message they send is that Japan will “attempt to maintain international peace and security as well as contribute to the international efforts for achieving international peace aimed at a solution of the issue”6 as announced, and these sanctions have been introduced in coordination with the US and the EU, which are the driving force behind the sanctions against Russia7, and the international community. The Whitehouse showed its appreciation of Japan in a fact sheet on Japan-US relations that referred to Japan-US cooperation on sanctions against Russia , and in its statement that “Japan has joined us through the G7 and has imposed some of their own sanctions. … So increasingly, this is a global chorus of voices that are speaking in opposition to what Russia is doing to its Ukraine policy.”8 Furthermore, Professor Lukyanov of Higher School of Economics in Moscow commented, “Tokyo has played its cards in the best possible manner. It has restrained the sanctions against Moscow as far as possible so that they are more symbolic than substantial”9, the fact that Japan has not imposed a significant economic cost on Russia is being interpreted as a message that the Abe administration places importance on Japan-Russian relations.

Conclusion

To summarize the above, Japanese sanctions against Russia appear to have been crafted with great care, from the timing at which each phase was implemented to the selection of the measures and their targets, for the purpose of allowing coordination with the US and the EU and keeping the door open for dialogue with Russia, and as that message has been duly transmitted, they are considered to have been successful. This report confines itself to an evaluation of sanctions as a diplomatic tool, but sanctions do not exist in isolation; what is important is that they contribute to a wider security strategy along with other diplomatic tools. The sanctions against Russia contribute to, rather than obstruct, the pursuit of several strategic goals, including strengthening (1) the Japan-US alliance, (2) the international order, and (3) relations with various countries, including Russia. Furthermore, while this report has focused on economic cost as the basis for classifying sanctions, in fact, the imposition of sanctions on Russia has also had political costs, including the postponement of President Putin’s visit to Japan and suspension of negotiations on a peace treaty. At present, Japan is pursuing a number of strategic objectives while keeping this cost to a minimum and maintaining a delicate balance. It would be difficult for Japan to independently lift its sanctions against Russia when the main objective of those sanctions is cooperation with the West. The US and the EU have made the full implementation of Minsk II a condition for lifting the sanctions against Russia. Minsk II lays out a roadmap for resolving the conflict in Ukraine from a cease fire to restoration of Ukrainian control over its border. Some EU member states are proposing that the sanctions against Russia be eased in accordance with progress on the implementation of Minsk II, and since this would affect Japanese sanctions as well, Japan is also keeping a close eye on developments in sanctions policy of its Western allies.

- Galtung, J., “On the Effects of International Economic Sanctions, with Examples from the Case of Rhodesia.” World Politics 19, 3: 378-416.

- Gaddy C.G., Ickes B.W., “Can Sanctions Stop Putin?” The motivation for sanctions is to impose hardship in order to change behavior. But the likelihood that this would apply to Russia is very weak. … Sanctions thus lead to greater control by Putin over the economy. … They also reinforce Putin’s political power. They rally the public around Putin.”

- Giumelli F., “How EU Sanctions Work: A New Narrative” Chaillot Papers May 2013, EU Institute for Security Studies

- Office of Financial Sanctions Implementation HM Treasury, Financial Sanctions: Guidance, April 2016

- Cortlight D.and Lopez G.A., Smart Sanctions: Targeting Economic Statecraft, 13

- Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan Press Release, September 24, 2014

- The White House, FACT SHEET: U.S.-Japan Bilateral Cooperation, April 25, 2014

- The White House, Background Conference Call on Ukraine, July 29, 2014

- Лукьянов Ф.Приоритеты и жизнь// Российская газета. №. 6962 (94)